Silicon Valley, this remarkable region in Northern California, has truly been the birthplace of technological revolutions. From the foundational silicon chips and semiconductors that paved the way for mass electronic device production, to Apple's personal computers and smartphones, Google's ubiquitous search engine, Facebook's social media revolution, and Tesla's electric vehicles, its impact is undeniable. Even breakthroughs like SpaceX's reusable rockets and the latest artificial intelligence wave originated right there. This begs the question: What makes it so special, and why can't this success be easily replicated elsewhere, like in India?. As the sources reveal, it's not a lack of capital, talent, or even marketing prowess in India that holds it back. The core difference, the "secret sauce," lies in a fundamental business culture and mindset – specifically, how one approaches companies, failure, and risk.

Let's unpack the key mindset differences that make Silicon Valley tick:

Embracing the Misfits and Defying the Crowd

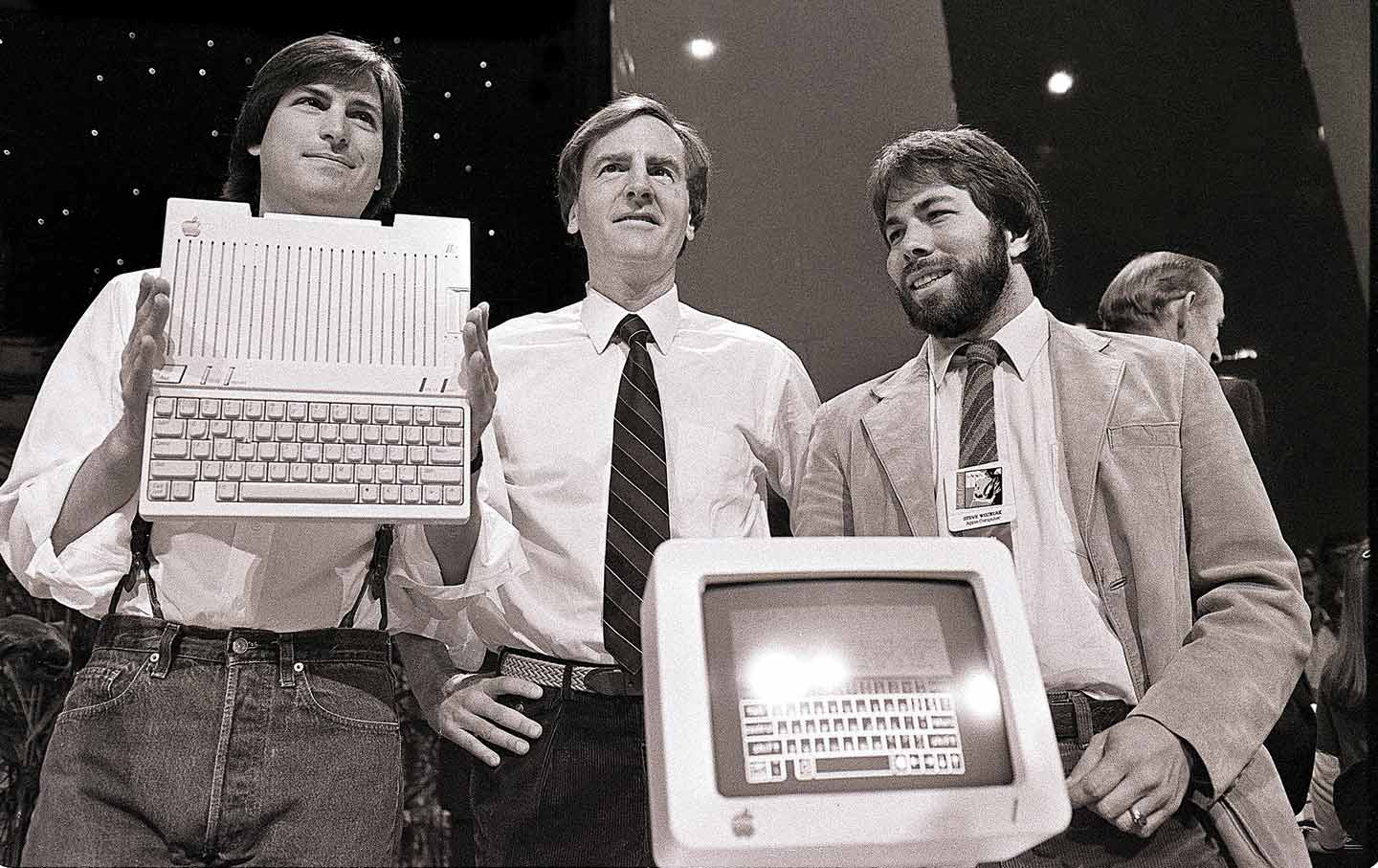

Silicon Valley literally thrives on crazy, unconventional thinkers, openly welcoming "misfits" who don't fit traditional molds. This environment understands a crucial truth: someone from "field A" entering "field B" is very likely to be disruptive compared to an insider, as they see things differently. For instance, someone from the payment industry entering the rocket industry would have an advantage over insiders because they'd bring a fresh perspective. Silicon Valley has never been about playing safe; it actually really likes the concept of a contrarian – somebody who thinks very differently from the crowd. These are the people who chase "moonshots" that sound absurd until they actually work, like flying cars or private rockets to Mars. This willingness to pursue grand visions is a defining trait of the Valley.

In the Valley, this optimism is almost borderline delusional to outsiders, yet it's precisely what makes it tick. Silicon Valley literally runs on ideas you believe, but other people don't. Sam Altman, for example, told that even the idea of doing OpenAI was ridiculed by researchers, who even called them "a rapper". Yet, people in the Valley believed in them and invested money, leading to where they are today. Early personal computers, social networks, and the first electric sports car were all dismissed as "toys" before transforming into world-changing entities like Apple, Facebook, and Tesla. The "red pill truth" here is that breakthrough innovation requires defying skepticism and ridicule. Silicon Valley's culture encourages this, whispering to the hacker working on a wild idea that they might be right, even if the entire world thinks their idea "sucks". If everyone believes a certain thing is correct, by the time that consensus has formed, you are late – you might be the 15,000th competitor. But if you take on ideas others don't believe in yet, you can be number one.

In stark contrast, India's social and educational systems tend to reward conformity, emphasizing rote learning over independent thought. Any "out-of-the-box" thinking often receives less support or understanding for their ideas. When early versions of products are shared in India, the response can be outright dismissal rather than the understanding that it's a 0.1 version on its way to 1.0. For example, when AI avatars were first used for content in India, almost everyone said it wouldn't work, despite later proving commercially successful.

The Power of Relentless Experimentation

Given that many groundbreaking ideas might initially be wrong, Silicon Valley emphasizes relentless experimentation. The only way to discover if an idea is wrong or right is to try many experiments, often running multiple experiments at once in parallel. Founders are encouraged to have "strong opinions but loosely held". This means you can strongly believe in something, but if the evidence doesn't support it, you must be willing to ditch it. The culture embraces the idea that most decisions are "two-way doors" – reversible. It's better to make decisions with 70% of the data rather than waiting for 90%, as waiting leads to slowness and allows competitors to move faster. When something works, the key is to double down, but before that, the only path is through trying many things and seeing what sticks. This approach prioritizes output and commercial success over memorizing definitions.

In India, by contrast, there's a preference for "viva voce" (oral examinations) over experimentation, emphasizing mugging up concepts rather than hands-on trying. There's a problem with pride being associated with publicly stated ideas, making it difficult to go against what was once said, even if evidence proves it wrong.

Default to Optimism and a Supportive Ecosystem

Ideas alone don't build companies; people and networks do. Silicon Valley's ecosystem is characterized by a default to optimism and a strong willingness to help. This belief acts as "grease" that makes ideas move, reducing friction. Social capital flows freely. Knowledge, connections, and favors are shared generously with an understanding of future reciprocation. Founders swap war stories and tips over coffee, experienced engineers mentor newbies, and successful alumni reinvest their winnings as angel investors in startups. Status comes not from job titles or pedigree, but from being a young entrepreneur trying something new. Established players offer belief, introductions, advice, credibility, and seed funding. Everyone understands that 90% of ideas will fail, but the focus is on supporting the attempt, asking "why not?" and "how can we help you try?".

India, however, is largely a default to skepticism environment. New ideas are often viewed as scams or fraud, even when no money is being taken from others. This skepticism can lead to outright falsehoods and discourage nascent efforts. Unlike Silicon Valley, where people understand that early versions are works in progress, in India, there's an oversupply of similar ideas because they are less likely to be criticized. In India, you often need to prove a lot more success before others are willing to help or provide introductions.

The Valley's Unique Attitude Towards Failure

Perhaps the most significant differentiator is Silicon Valley's relationship with risk and failure. Failure is not the end; it's almost like a badge of experience. As Elon Musk famously said, "Failure is an option here. If things are not failing you are not innovating enough". Most successful entrepreneurs are repeat entrepreneurs, and investors are willing to fund them again, recognizing that they have learned something. Big breakthroughs require big risks, and the culture mitigates the downside of embarrassment, career damage, or financial ruin. It radiates a baseline optimism that while not every idea will succeed, it's worth trying, and failure doesn't exile you from the community. Paul Graham noted that society needs to cultivate "forgiveness for the trial and error process of innovation".

India, by contrast, is a culture that hates failure, often penalizing risk-taking and therefore innovation itself. A failed venture in India carries a stigma that can haunt an entrepreneur's entire career, whereas in Silicon Valley, it's seen as a "right of passage". Risk-taking is not ingrained, and failure is usually permanent. This cultural difference means people are fighting for their first shot, and a second chance is much harder to come by.

Marketing and Meritocracy: Beyond the Product

The best startup founders globally are often both marketing and product geniuses rolled into one. They understand consumer delight, shareability, and low friction, which are crucial for both product success and effective marketing. Even the attraction of Silicon Valley itself, drawing top talent like Sundar Pichai and Satya Nadella, is partly due to its manufactured allure and effective marketing. In terms of talent and venture capital, Silicon Valley leans towards meritocracy. If you're a good founder with a contrarian idea, you can raise capital relatively easily. It's considered "cooler" to work at a small startup trying something new than at a large corporation like Google. Being a passionate, serious entrepreneur, even if unproven, earns you enough respect for introductions.

India, however, is often deeply nepotistic with talent and VC. Knowing someone often smooths the path to funding or jobs. Social status in India can push talent towards proven corporate paths or government jobs rather than risky startups, where a prestigious title might be valued more than founding a small company. In India, you often need to prove a lot more success before others are willing to help or provide introductions.

In conclusion, while India absolutely possesses the necessary capital, talent, and growing capabilities for good marketing and distribution, the real challenge lies in fostering a business culture and mindset that embraces risk, failure, radical ideas, experimentation, and a supportive, optimistic ecosystem. Cultivating this "grease" of belief is the key to unlocking its full innovative potential.

Comments

Post a Comment